Weaving in the field of Science/Art: Are woven textiles a valid art-form through which to explore/explain science?

“The two great ways of exploration, discovery and knowing: science and art”1 Terry Trickett

Weaving as art has been recognised for thousands of years through the creation of woven tapestries; status symbols of beauty and practicality for the elite of society in different parts of the world which are still in demand and woven today.2 In China, exquisite artworks were woven on drawlooms several centuries BCE. Both forms were illustrative and pictorial, depicting scenes from mythology, religion, portraits, and battles, as well as textile renditions of fine art, including modern works by artists such as Henry Moore and Tracy Emin.3 During the twentieth century, in 1960s Europe and the US, tapestries developed an additional life – as non-traditional three-dimensional textile installations, “constructed into soft sculpture, paralleling experiments in fine art,”4 often monumental in scale, through artists such as Sheila Hicks, and Lenore Tawney.5

But what of cloth weaving? What of the fabric that is made on shaft looms with limited patterning abilities, that is not pictorial and is traditionally used as functioning fabrics – cloth to protect yourself, to adorn your home, to use – what of that? Historically, functional fabric could be decorative, but always subservient to its end use. It might be regarded as art by its maker, or its wearer in the case of decorative clothing, but rarely art for art’s sake, separate from its functional use. In this paper, I propose to show that both types of woven textile can be viewed as art today, specifically in connection with science.

For me and the two weavers I feature in this essay, weaving is a means of communication, of exploration into a hidden world, a way of making the invisible visible through tactile as well as visual means. Lia Cook uses pictorial methods on a jacquard loom6 and a project she is involved in highlights neural networks in the brain.7 Philippa Brock uses functional cloth, also woven on a jacquard loom, and her collaboration was with Nobel Laureate Sir Aaron Klug exploring the structure of the tobacco mosaic virus.8 I prefer an abstract approach, looking into the underlying structures of the earth through plate tectonics and geology and bringing them into 3-dimensional relief. But whatever the subject matter, equipment and methods we use, for us all the process of weaving the work is a means of learning about science, about how integral everything is, interwoven through our very beings, from atoms to brains to mountains. Through weaving we discover an exciting new way of looking at these deep subjects, expressing them through tactility – a way that cannot be achieved through digital imaging.

The use of art to explain and explore science has developed into a specific field, called sci-art. The field developed originally in the US in 1988 with the founding of Art & Science Collaborations Inc9 which was instrumental in re-invigorating the art and technology field in the US during the 1990s. Beginning in 1997/8, the Wellcome Foundation was the first body in the UK to fund projects combining both science and art, instigating a ten-year period of funding. At the request of the Wellcome Trust, architect and designer Terry Trickett and Charles Landry set up Sci-Art Lab®10and the earlier Sci-Arts Consortium which included Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, British Council, Arts Council of England, National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA) and, of course, the Wellcome Trust,11 which was involved with three years of funding sci-art projects, and which included collaborations between scientists and artists, both in performance and visual arts. Since then, many such exhibitions continue to be mounted by the Wellcome Trust.

With organisations such as the Wellcome Foundation and the Arts Council backing it, sci-art has become a valid area of discovery and collaboration between top scientists and academics as the Nobel Project12 demonstrates. Initially instigated by Amanda Fisher from the Medical Research Council and Carole Collet from Central St Martins College of Art & Design, the two-year collaboration paired 5 Nobel Prize winning scientists with 5 textile designers. As Brona McVittie (Science Communicator, MRC Clinical Sciences Centre) explains, “designers fundamentally shape the way we live, while science pervades the very fabric of our lives. Nobel Textiles involves a journey into the interface between science and design, a dialogue between leading researchers in both fields.”13 The idea behind the project and the exhibition was to “explore creative overlaps in science and design evoking new meaning and enriching culture.”14 Sir Aaron was awarded his Nobel prize in 1982 for describing the crystal structures of protein-nucleic acid complexes. Philippa Brock’s area of research is in developing innovative woven textile fabrics that explore the industrial power loom manufacturing method, developing fabrics that change shape as they come off the loom through the varying interactions of yarns and weave structures.

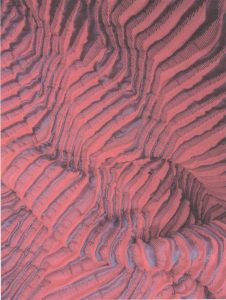

Philippa Brock – “Self Assembly” (Detail), 2008 (For biography, see Appendix A)

Philippa Brock – “Self Assembly” (Detail), 2008 (For biography, see Appendix A)

This metamorphic quality of fabric is something I am passionate about developing through shaft loom weaving, utilising the differing properties of fibre, yarns, structure and finishes.

The focus of the collaboration used the structure of the tobacco mosaic virus through imaging techniques that Sir Aaron had developed to look at viruses using a process that translated 2D into 3D information.15 The underlying process of virus formation is self-assembly. This area struck a chord with Brock, whose aim became to make textiles that self-assemble or fold without being manipulated by hand or machine after weaving. This is achieved through using combinations of yarns and weave structures which ‘fight’ against each other. For instance, weave structures, which are composed of different interlacements (the combinations of how the horizontal weft yarns go over and under the vertical warp yarns16 ) can be designed to create imbalances in the fabric which lead to the cloth buckling or folding in certain ways, both predictably and non-predictably. (See Appendix B and Addendum for interview with Brock.) In my practice, this dimensional ability of the fabric to manipulate itself through structure expresses a subconscious fundamental understanding of the way the world works.

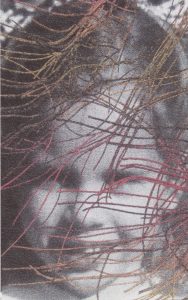

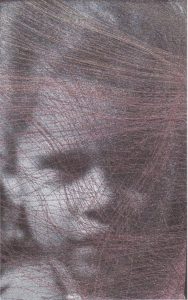

Lia Cook, like Brock, is also a jacquard weaver, but rather than producing cloth, she creates large-scale images of “large woven faces that look photographic at a distance but dissolve into maze patterns up close and finally into visibly intersecting threads.”17 (For biography, see Appendix C) Her practice incorporates scale both in the hugeness of the image and also in using images of the interlacements of weave structures to create a background ‘maze’ which affects the tonal gradations of the work to create the visual portrait effects. During a travelling exhibition tour of her Faces and Mazes work in the United States and Canada during 2009/2010 Cook was struck by the different emotional reactions of the audience when confronted with the artwork; “One aspect of the emotional response seemed to be the desire to touch that the experience of engaging with these works engendered.”18 Cook’s long-term interest in neuroscience and the brain led to an invitation to become the artist-in-residence in the University of Pittsburgh TREND Program19 where she was able to work with neuroscience researchers to try to map the emotional response to her works in the brain. (See Appendix D)

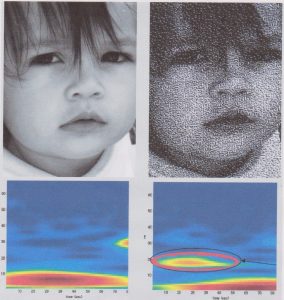

Fabric Task EEG for Trend Program. (Left image – photo of Cook as a child – accompanying EEG underneath of subject viewing the photo. Right image – woven image of Cook taken from photo – accompanying EEG showing increased emotional response to woven image.)

Fabric Task EEG for Trend Program. (Left image – photo of Cook as a child – accompanying EEG underneath of subject viewing the photo. Right image – woven image of Cook taken from photo – accompanying EEG showing increased emotional response to woven image.)

The revelations that her research has uncovered really excite me, both from the scientific discovery itself, and because it brings weave firmly into the frame as a valid research medium.

My own field is in geology and the underlying causes and movement of plate tectonics, mountain building and erosion, interpreting that into the medium of weaving. Using every stage of the process, from fibre selection, spinning techniques for yarns, weave structures and finishing techniques, I am exploring the potential of weave to be a tool for understanding, and expressing, geological evolution. Through this, I am both expanding my technical knowledge of weave structure and providing an insight into the real-time processes of geology. It takes millennia for mountain ranges to build up through the collision of continental tectonic plates, but some of the techniques that I am using to manipulate the fabric, through structure, into three dimensions create these visual effects immediately, providing an interpretation and direct visual stimulus of natural forces that can assist in understanding the machinations of the natural world. (See Appendix E)

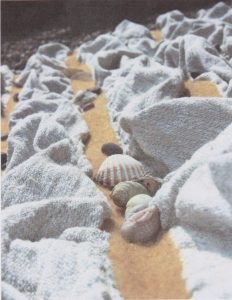

Stacey Harvey-Brown “Foreshore” (floor piece) 2011 Cotton, wool, polyester, pebbles, shells

Stacey Harvey-Brown “Foreshore” (floor piece) 2011 Cotton, wool, polyester, pebbles, shells

The thinking methodology for both the practical elements of weaving and science are surprisingly similar – a logical methodical progression of steps, rigorous attention to detail, and repetition. These are complemented by sudden insights which, in science, lead to breakthroughs and unforeseen developments, and in weaving which lead to novel approaches and unusual combinations of structure, fibres and yarns. Cook has identified the close emotional affinity that humans have with woven textiles on a sub-conscious level, encompassing the physical sense of touch as well as the visual in experiencing the work. That this visceral element is so much a part of the experience of her work is a strong indication that woven textiles have a deeper impact on the subconscious mind than was previously believed. If this is, in fact, the case, weaving has taken on a new and vital role as a method of communication – more than an image or just a piece of cloth, it can speak directly to the subconscious mind.20 Encompassing the visual through pictorial and abstract means, the tactile through materials, texture and dimensionality, and the emotions through neural pathways in the brain, it appears that weaving has a major part to play not only in the exploration and explanation of science through an accessible and empathic medium, but also as a means of artistic expression itself.

“The success of Sci-Art lies in its ability to tap the urge, felt by scientists as well as artists, to find new methods of discovery”21 Terry Trickett

Notes:

- Sci-Art Lab® http://sites.google.com/site/researchtakingthenextstep/ [Accessed 30th September 2011]

- West Dean Studios. http://www.westdean.org.uk/Tapestry/About/TapestryThrougtheAges.aspx [Accessed 10th October 2011]

- Henry Moore tapestries executed by West Dean Studios http://www.westdean.org.uk/Tapestry/Showcase/HenryMoore.aspx [Accessed 10th October 2011] Tracy Emin tapestries executed by West Dean Studios http://www.westdean.org.uk/Tapestry/News/NewsandEvents.aspx [Accessed 10th October 2011]

- Racz, I/, (2009) Contemporary Crafts, Berg, p66

- See Waller, I., (1977) Textile Sculpture, Studio Vista

- The jacquard loom was developed from the draw-loom in 1804 in France. It allowed the loom to be programmed with punch-cards to weave pictorial images, rather than tapestry weaving which is totally dependent for its design and execution on the human weaver. For further reading, see Essinger, J., (2004) Jacquard’s Web: How a Handloom Led to the Birth of the Information Age, Oxford University Press

- Cook, L., 2010 “An Investigation: Woven Faces and Neuroscience”, ETN Textile Forum 4/2010 (December), p42/43

- Brock, P., Self-Assembly project with Sir Aaron Klug. See Nobel Textiles: Marrying Design to Scientific Discovery http://www.nobeltextiles.com/nobeltextiles_/Home_files/NOBEL%20CATALOGUE%202008.pdf [Accessed 2nd October 2011]

- “Art & Science Inc. is an international group of artists, scientists, technologists, professors, writers, curators, gallerists, and others working in or fascinated by the intersection of art, science, technology, and the humanities.” http://www.asci.org/ [Accessed 30th September 2011]

- “Sci-Art Lab® is a centre of science/art intelligence. It scans, monitors and evaluates existing collaborations between artists and scientists worldwide as well as fostering new collaborations that have potential for commercial application. It nurses projects from the generation of initial ideas to financing and implementation, acting as mentor and advisor.” http://sites.google.com/site/researchthelegacyofsciart/ [Accessed 30th September 2011]

- Wellcome Trust Arts Awards: http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/Funding/Public-engagement/Funding-schemes/Arts-Awards/index.htm [Accessed 30th September 2011]

- Nobel Textiles: Marrying Design to Scientific Discovery catalogue http://www.nobeltextiles.com/nobeltextiles_/Home_files/NOBEL%20CATALOGUE%202008.pdf [Accessed 2nd October 2011]

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “By X-raying the structures at different angles, [Sir Aaron] assemble[d] a series of slices to give a clear picture of their structure, .. layering glass plates, each with an image slice, on top of one another. When viewed from above the 3D nature of the viruses was apparent.” Nobel Textiles: Marrying Design to Scientific Discovery catalogue http://www.nobeltextiles.com/nobeltextiles_/Home_files/NOBEL%20CATALOGUE%202008.pdf [Accessed 2nd October 2011]

- The principles of weaving (warp and weft) are that the warp threads are parallel threads running in one plane i.e. vertically, and the weft threads are parallel threads interweaving over and under the warp threads at 90o, i.e. horizontally. Different weave structures are created by interweaving the weft threads over and under different numbers of warp threads in adjacent rows (known as picks) and these create patterns. Different kinds of patterns used together can cause uneven tensions in the fabric, leading to buckling or folding of the fabric when it is removed from the loom. This can be designed for specific purposes which is what both Philippa Brock and I seek to do in our weave structures so that the resultant fabric, once removed from the tensions and restrictions of the loom, is forced from the flat plane it normally occupies into one that creates a three-dimensional shape through its own agency.

- Cook, L., 2010, “An Investigation: Woven Faces and Neuroscience”, ETN Textile Forum 4/2010 (December) p42/43.

- Ibid.

- TREND – Transdisciplinary Research in Emotion, Neuroscience and Development; group of the Department of Psychiatry at the School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh.

- See Appendix D

- Sci-Art Lab® http://sites.google.com/site/researchbridgingthegap/ [Accessed 30th September 2011]

Appendix A http://www.arts.ac.uk/tfrg//node/3568 (with permission) [Accessed 30th September 2011]

Philippa Brock Subject Leader BA Woven Textiles, Central St Martins College of Art & Design

Biography

“Philippa Brock is Woven Textiles Specialist Subject Leader (0.6) at Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design and also works as a textile designer, consultant and researcher. She graduated from Goldsmiths’ Collect (1991) and The Royal College of Art (1993). Brock has worked in both the textile industries and in various roles in Higher Education including Senior Research Fellow in CAD/CAM Woven Jacquard Textiles at Winchester School of Art 1994 – 96.

“Brock designs woven and printed textiles for the international market, (DMC, Otton, Fisch-Bacher, Weisbrod Zurrer, Witchery, Teseo, Miroglio, Jaeger, amongst others), has worked with yarn companies designing concept woven textiles for showrooms and exhibition at Expofil and Pitti Filati, in particular exploring innovative use of companies’ yarns within the CAD/CAM Woven Textiles industrial production method (Lurex, Safilin, Lame Ledal) and up until recently was consultant designer for the Taiwan Textile Federation, designing and producing their twice yearly fabric collections, trend themes and colour presentations. At present Brock is researching and developing smart textile systems exploring in particular the aesthetics, handle, drape and conductivity within both fashion/clothing and interior settings.

Research Statement

“Philippa Brock is currently working in three areas of research, one of which is:

“CAD/CAM Woven Jacquard ‘on-loom’ Finishing Effects: The research investigates ‘on-loom’ finishing effects within the industrial CAD/CAM woven jacquard process. The resultant prototypes require only scouring and stentering. The research poses the hypothesis that previously finished surface effects i.e. post woven embellishments (pleating, embroidery etc) can be achieved at the earlier weaving stage.

“The outcomes of this research have a dual focus: creative and innovative fabrics; and new approaches to the industrial production method. The fabrics developed in this research are not to replicate existing fabric methods but are a product in their own right. The research includes investigation of CAD/CAM, yarn and woven structure innovation to achieve these ‘on-loom’ effects and the potential for cost, time and energy efficiency. Both the research and professional practice require a keen awareness of new developments in yarn, fabric and finishing processes and existing and potentially new markets.”

Appendix B

Self Assembly – Nobel textiles

Extract taken (with permission) from Central St Martin’s website http://www.arts.ac.uk/tfrg/node/11080 [Accessed 30th September 2011]

“Self Assembly is a series of large jacquard woven pieces based on Sir Aaron Klug’s research, which involves creating 3-dimensional models of viruses from 2-dimensional information. Philippa Brock is exploring methods of transforming 2-D weaving approaches into 3-D models – creating self-folding/forming experimental textiles pieces. Philippa’s work as been kindly supported by the Gainsborough Silk Weaving Company.”

Appendix C http://www.liacook.com/statement/ [Accessed 30th September 2011] (Reproduced with permission)

Lia Cook

“My current practice incorporates concepts of cloth, touch, and memory. I use the detail, an intimate moment in time, often woven in oversize scale to intensify a shared emotional and sensual experience. I use a digital loom to weave images that are embedded in the structure of cloth. The digital pixel becomes a thread that when interlaced with another becomes both cloth and image at the same time. This woven image brings with it many of the sensual experiences that we associate with cloth. Childhood family snapshot and video stills are some of the raw materials that I draw on to investigate small, intimate details of the body or to capture a fleeting human expression. My practice involves research into new technologies and new ways to translate my images that make the structure visible and physically felt, attempting to create the image as physical object.

“The candid intimacy of the family snapshot seems an unlikely starting point for Lia Cook’s over-scale woven images, until one considers that such weaving, whatever its size, is the result of the organisation of small elements, close attention to detail and the dexterity of handwork. Just as informal family photos are a medium of transaction and an exchange of intimate information and shared history, cloth enfolds us into its history as we allow it to envelop us and record the marks and creases of our presence. The source of Cook’s images is a simple camera from the 1950s, which has a link to today’s imaging technology in the same way that computers have their origins in the manually operated Jacquard weaving looms of the early nineteenth century. In Big beach boy Cook links these technologies, exchanging pixels for thread and focusing closely on the bland subject matter of a tiny and apparently insignificant family photo of a baby. On closer inspection, when we seem to be skin-to-skin with the child in an uneasy embrace, the subject dissolves into a pointillist colour field of shimmering individual threads, allowing our senses to take us beyond the threshold of recognition.” -Robert Bell, Curator, National Gallery of Australia, Web text for exhibition “Transformations: The Language of Craft” 2004

“The viewer is struck by the sheer physicality of her art as well as by her intellectual engagement. Sensual and sumptuous these…. works…. spur questions and concerns that bring down the curtain on conventional notions regarding painting and privilege.” -Miles Beller, review of “Material Allusions” traveling exhibition, in Artweek Magazine.

“Absorption and inclusion are pervasive strategies in Cook’s work, operating at almost every level: formally, in her constant exploration of new techniques; emotionally in the way she stimulates the sense of touch through the eyes; and intellectually in the multiple reference to different art histories. Her work reminds us that in English the phrase “to weave together” means “to integrate”. -Meridith Tromble, essay for the Flintridge Foundation Awards for Visual Artists 1999/2000 catalogue.

Appendix D

Cook, L., “An Investigation: Woven Faces and Neuroscience”, European Textile Network journal Textile Forum 4/2010 (December) P42/43 (Reproduced with permission)

“My exhibition Faces and Mazes has been travelling in the United States and Canada for the last year and a half. At each venue I was struck by the different emotional reactions to confronting these large woven faces that look photographic at a distance but dissolve into maze patterns up close and finally into visibly intersecting threads. One aspect of the emotional response seemed to be the desire to touch that the experience of engaging with these works engendered. At this point, my long term interest in neuroscience and the brain came together in… a collaboration with neuro-science researchers to look at the emotional response to the faces. I was invited as an artist-in-residence to University of Pittsburgh TREND Program1 to use their lab, facilities and expertise to devise and carry out experiments in an attempt to map the emotional response to these works in the brain. My original hypothesis was that the woven interpretation of the face would add something different to the emotional response compared to a flat photographic print. I wanted to explore the nature of people’s emotional connection to woven faces. I thought that the material and structural aspects of the textiles, the physical evidence of the hand and the memories associated with these tactile experiences might intensify the reactions. Something about the textile engenders embodied emotional response beyond that of the 2-D photo.

“Doing preliminary but scientifically based single subject studies, we were able to map the response in the brain showing areas of touch and emotion in response to viewing the artwork. We tried many different approaches using Electroencephalography (EEG), Pupil Studies, EyeTracking and Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The subjects did a variety of tasks. In one example they compared the actual woven image with a photograph of the woven image with the original image itself. We could see the different response in the brain in visual images from fMRI data and in records of electrical brain activity from EEG and found some evidence of my original idea that the woven image evoked a different kind and/or intensity of emotional response. Other tasks as well as interviews with the subjects afterwards expanded my understanding of the emotional connection to woven faces. ….

“The concept of the TREND residency, direct by Greg Siegle, PhD, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, is that inviting artists into the lab to connect with scientific researchers has a positive effect on both the scientists and the artists. The artist may encourage the scientist to think in new creative ways and the artist can learn the tools of the scientist to develop their artistic ideas or to look at their artwork in new ways. My experience of the residency is that I have a new understanding and appreciation for the kind of creative process that goes into scientific research. In addition, the intense connections with researchers gave me new energy and new insights into my work. When I started the project I considered it “art research” and did not know exactly where it would lead me, whether the result would be video documentation or actual woven artwork. I was surprised to be able both to learn more about the answers to my questions and also to begin to create new work inspired by the experience.

“One unexpected visual result involved the experimental use of Diffusion Spectrum Imaging (DSI) in which the fibers of the brain connections that run through the white matter of the brain can be imaged using MRI technology. Upon seeing an early example, I was struck by the similarity of these interlacing fibers to textile constructions. I underwent this imaging process using my own brain as example. Using software from MGH/Harvard, Biomedical Imaging Lab,2 I was able to manipulate the images of these fibers, to zoom in and rotate them. These images became a starting point for my latest woven work that combines the woven face with the fiber of the interior brain as in the example “Tracts Past”.

“Although these are initial responses and I expect to continue to draw inspiration from this research for my work, I am also excited to explore new, different projects and possible neuroscience-based collaborations. I am fascinated with the territory in which science and art can meet.”

Notes:

- TREND – Transdisciplinary Research in Emotion, Neuroscience and Development; group of the Department of Psychiatry at the School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh.

- Software “TrackVis”, Ruopeng Wang, Van J Wedeen, Trackvis.org Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard.

Lia Cook “Facing Touch” 2011 54” x 51” Cotton, Rayon. Woven

Lia Cook “Facing Touch” 2011 54” x 51” Cotton, Rayon. Woven

Lia Cook “Facing Maze” 2010 7” x 50” Cotton, Rayon. Woven

Lia Cook “Facing Maze” 2010 7” x 50” Cotton, Rayon. Woven

Lia Cook “Facing Maze” detail

Lia Cook “Facing Maze” detail

Lia Cook “Neural Networks” 2011 81” x 51” Cotton, Rayon. Woven

Lia Cook “Neural Networks” 2011 81” x 51” Cotton, Rayon. Woven

Lia Cook “Tracts Past” 2010 81” x 51” Cotton, Rayon. Woven

Lia Cook “Tracts Past” 2010 81” x 51” Cotton, Rayon. Woven

Appendix E

Stacey Harvey-Brown

Images of 3-dimensional work showing interpretation and direct visual stimulus of the natural forces that can assist in understanding the machinations of the natural world through weaving.

“Rock cabinet with samples” (table piece). 2011 Cotton, polyester, wool, copper, silver, stainless steel/wool

“Rock cabinet with samples” (table piece). 2011 Cotton, polyester, wool, copper, silver, stainless steel/wool

”Bark IV” 2011 Cotton, wool, paper

”Bark IV” 2011 Cotton, wool, paper

Bark III (detail) 2011 Cotton, copper

Bark III (detail) 2011 Cotton, copper