“Invention, and re-invention too, is the essence of all creative work.” Josef Albers, 19281

The Industrial Revolution was more than an explosion of technology – not only did it revolutionise the way things were made, it changed craft thinking in fundamental ways. “I cannot conceive of machines as anything but a blessing when quantity is involved,” Anni Albers commented.2 With the arrival of mass-production of utilitarian cloth, textile makers were released from work grounded in utility. Some chose to embrace industry: Albers and UK handweaver, Ethel Mairet, used their technical and material knowledge to add aesthetic and haptic qualities to mass-production employing hand-weaving experimentation in the service of industry.3 Theo Moorman (fig 1) and Peter Collingwood (fig 2) went down a more esoteric route, exploring how handwoven textiles could communicate through art,4although both had a practical core to their practice so that they could earn money to live; Moorman with liturgical commissions, Collingwood producing rugs.

Fig 1

Fig 1  Fig 2

Fig 2

In the confusion and melt-down that arose for makers as their traditional role disappeared, textile’s metaphorical associations came to the fore. Cloth is integral to the human experience – both everyday and ceremonial. It has associations of power, prestige, wealth, belonging, and equally to poverty, to segregation, and dis-empowerment. It is deep within our language systems, and universal. Every culture has references to cloth, cloth-making and preparation in its mythology, its language, its rituals. Therefore, using cloth as a medium for expressing deep fundamental insights uses both conscious and subconscious references. On the one hand, the very fact of its everydayness can lead to its invisibility. On the other, the fact that we are surrounded by cloth and have such a close relationship to and with it means that communication can happen on a deeper, subconscious level. “Textiles are multivalent: they have many different qualities and characteristics, each of which lends itself to metaphor and associations,”5 states professor and curator Beverly Gordon.

Historically, textiles were developed for utilitarian use – covering, clothing, containing. However, this is not their only function. Decoration may seem ancillary, but has crucial roles in conveying information, whether it is to denote clan, rank, wealth, status or belief. Clothing has a primary function of keeping one warm or cool (depending on climate). Its pattern can instruct the individual as to behaviour or to acknowledge community or clan. Other elements, such as the texture of cabling in an Aran sweater, may tell you the story or history of the clan, the wearer or maker. Decoration can be integral in the making or added later. It can have religious or ritual associations, also a possible factor in the making or constructing of the cloth.

Quilts are well known in the western world for their layered meanings. Originally created for warmth and protection, they can be a cultural indicator6 (Amish quilts, fig 3), engage a community in their making7 (Gee’s Bend quilts, fig 4), a social indicator (using scraps of materials or quality fabrics), as a memorial8 (the AIDS quilt), as a testament to skill, an heirloom, conveyor of information, and as a personal statement (Tracey Emin’s quilts). Quilts can be used for their primary function or put on show as a decoration or status symbol. They can also convey esteem by being used to confer status on a guest.9

Fig 3

Fig 3  Fig 4

Fig 4

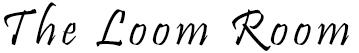

Tracey Emin’s approach to the quilt is not one of care in execution, but the importance of the message of textile – the ‘everydayness’ of cloth. In Everyone’s Been There (1997) 10, what matters to Emin is the metaphor embedded in the object made – the physical, personal closeness of its use underlining the revelatory texts integrated into the cloth (fig 5).

Fig 5

Fig 5

In some ways, she epitomises the polar opposite of our traditional associations with quilts. Historically quilts were beautiful, functional, sometimes quietly subversive, sending out coded messages in subliminal ways. Emin’s work is loud, with a sense of spontaneity – in contrast to the hours of careful attention normally invested in quilts. Her work can seem more subversive principally because she is using such a familiar medium. She hangs her pieces on the wall, displacing the primary function of quilts – that of protection, warmth, covering – and bringing secondary functions into sharper focus – social commentary, narrative, image control.

Many artists use textile’s metaphorical associations within society to explore a wide variety of social and philosophical issues. Grayson Perry creates dresses for his alter ego, Claire, to explore issues of transgender.11 Susie MacMurray brings our attention to materials and functionality through her garment sculptures, some of which can be worn, others which cannot, using materials usually unassociated with textile to highlight social issues.12 Freddie Robins confounds our notions of wearable, confusing the boundaries of form by creating apparently functional knitted sweaters which cannot be worn in the usual way as they are joined together. Our attention is drawn to the displacement of the garment, enabling it to exist in a different perceptual field, creating an awareness of the ‘craft’ of knitting in an art setting.13

Fig 6

Fig 6  Fig 7

Fig 7

Fig 8

Fig 8

These three artists embody Glenn Adamson’s statement that “in the very marginality that results from craft’s bounded character, craft find its indispensability to the project of modern art…. craft’s inferiority might be the most productive thing about it.”14 I feel that textile’s position of ubiquity in our everyday life plays such a role in its use for artistic expression.

Art historian Howard Risatti believes that craft objects have an imperative of function, but also acknowledges that whether they are functional or not, they all draw from the knowledge of materials and process that is the underpinning of functional craft.15 Maria Elena Buszek draws attention to the potential of craft traditions “to transform the ordinary into something surprising, subversive, and poignant, even when “craft” is addressed in performance rather than pots, or process rather than product.”16

The challenges of today embrace a generation that is politically active bringing craft into the political arena through action, not just observation.17 Global awareness of social injustice, sustainability issues, environmental pollution and technology has impacted on how craft is used as a means of social commentary and catalyst. Technology has a direct impact on craft through innovations such as 3-D printing,18 and textiles have seen the incorporation of electronics and reactive yarns. Technological fashion garments have inbuilt mp3s, and multiple pixel video screens which flash up images or messages, or glow with a colour to reflect your mood.19

Fig 9 But what does this say about our society, the people who consume the technology and the messages being transmitted? If a consumer does not need to know about the technology in order to design and use it, could this be seen as a truly democratised form of art? I find myself excited about the possibilities of new technology, but also reticent about whole-hearted immersion into it. As we find ourselves living in an increasingly virtual world, there is a growing need to engage with the real, with haptic and tactile qualities inherent in physical things. The greater the interaction with electronics, the greater the need seems to be to ‘touch base’, to get back in touch with the rhythms of nature, with haptic objects. Craft has a valuable role here – not to hark back to the old days, but to embrace new technological developments in materials and processes, and to mix them with tried and tested methods that have served humans well in the past. In the cross-cultural technological melting pot, new forms of craft evolve.

Fig 9 But what does this say about our society, the people who consume the technology and the messages being transmitted? If a consumer does not need to know about the technology in order to design and use it, could this be seen as a truly democratised form of art? I find myself excited about the possibilities of new technology, but also reticent about whole-hearted immersion into it. As we find ourselves living in an increasingly virtual world, there is a growing need to engage with the real, with haptic and tactile qualities inherent in physical things. The greater the interaction with electronics, the greater the need seems to be to ‘touch base’, to get back in touch with the rhythms of nature, with haptic objects. Craft has a valuable role here – not to hark back to the old days, but to embrace new technological developments in materials and processes, and to mix them with tried and tested methods that have served humans well in the past. In the cross-cultural technological melting pot, new forms of craft evolve.

An exponent of this in textile is the Japanese weaver, Jun-ichi Arai.20 As with Albers and Mairet, Arai embraces new technology and uses it to his advantage. What he brings to the mix is a deep sense of Japanese aesthetics. Although the Asian world is also diving helter-skelter into the middle of the technological boom, there is a stillness about traditional Japanese aesthetics which is so different from the Western approach – there is still a connection to the essence of thing. Whether in nature, or in objects, the essential quality of it is appreciated. Methods are investigated, and juxtapositions of elements explored. In Arai’s textiles, new technology and traditional materials are combined with new materials and traditional methods to exciting new effects (fig 10).

Fig10

Fig10  Fig11

Fig11

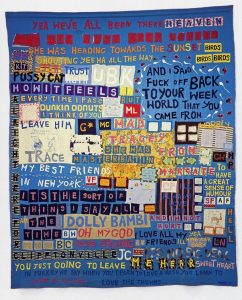

And yet, this combination of old and new is not confined to design and industry. Japanese textile artists pay attention to the immaterial through materials and process investigation. Machiko Agano is an example of this, exemplified in her piece Untitled 2000 (fig 11). “I am attracted by the mysterious shapes of nature: patterns made by the wind on desert sands; shapes or eroded rocks on coastal shores; clouds driven across the autumn sky. This is my art: the exploration and expression of the fundamentals of nature.”21

This philosophical approach is echoed by Ferdinand de Saussure describing structuralism as a method, which “seeks to comprehend particulars by describing their interrelationship within the totality of general codes which govern them. It looks for the deep and often hidden structures beneath the surface manifestations of meaning.”22 For me, this could be describing weave. Materials and their interrelationship with structure fall within the totality of the codes of weave which govern them. Deep and often hidden structures are what give the fabric its qualities of tactility and form. Claude Levi-Strauss was also interested in disclosing “hidden universal strata of meaning which lie beneath the rapidly changing surface phenomena of our world”23 – a perfect metaphor for textile art in a contemporary world.

The Industrial Revolution challenged craft’s purpose in the past and new technologies are changing our approaches for the future. Diversity and fragmentation instigated by the Industrial Revolution continues to enrich our textile world. Re-introducing textile in different ways makes it more visible and reminds people of what textiles might be and the depth of their connections to textile.24 I think that the interest in hand-work and haptic qualities will grow as a way of grounding us in the midst of a virtual world that seeks to integrate our everyday experience into the digital. Metaphoric qualities as seen in Emin’s work help people to feel grounded and part of a human existence, but Agano’s work has a spiritual dimension that the virtual world cannot provide. Both are needed in human experience.

Anni Albers, in 1944, summed up the fundamental challenges that still face us today.. “Things take shape in material and in the process of working it, and no imagination is great enough to know before the works are done what they will be like. …we are led, in going along, by material and work process. … We learn to listen to voices: to the yes or no of our material, our tools, our time.”25

Notes

- Albers, J. In Adamson, G. (2007) Thinking Through Craft Oxford & New York: Berg, p84.

- Albers, A. (1957) Refractive? In: Albers A. (1979) On Designing Connecticut: Weslyan University Press, p27.

- “Ideas for new textiles originate in the handloom workshops because it is there that the experimenter is to be found with the possibilities of leisure to evolve new ideas.” Mairet, E (1942) Handweaving and Education, London: Faber, p13.

- Moorman developed a decorative woven inlay technique that bears her name in order to bring pictorial elements to her loom-woven (as opposed to tapestry) work.Collingwood developed several ways to create artworks by adapting his looms to different requirements. Anglefell, shaft-switching and macrogauzes were all developed from loom adaptations. For further descriptions of these methods, see Appendix A.

- Gordon, B. (2011) Textiles: The Whole Story, London: Thames & Hudson, p23

- Amish quilts were an outward expression of their cultural beliefs, showing restraint in decoration and colouration, but skill and patience in the working of the quilts.

- The African-American women who lived in the hamlet of Gee’s Bend in Alabama worked together to create quilts for their families. As sharecroppers and tenant farmers for absentee white cotton planters, the sense of community fostered by geographical and social isolation let to the communal creation of these quilts and to a very distinctive style using patterned fabrics and simple geometries with a spontaneity that has become appreciated in art circles. What was done for necessity now earns the women good money and their quilts are in demand by collectors.

- Begun in 1987 to commemorate the lives of people lost to AIDS, the AIDS memorial quilt was a means to record the stories behind the people who had died. Now so huge that it cannot be shown in its entirety, sections of it are shown in exhibitions which tour the US. Made up of separate panels which are joined together in sections, it is the largest community art project in the world. Combining many different techniques, colours, styles, it is a mosaic that reflects the personalities of the dead, the makers and the communities brought together through AIDS. See http://www.aidsquilt.org/about/the-aids-memorial-quilt for further information. Website accessed 23rd November 2012.

- Further reading: Peterson, K.E. (2011) The Modern Eye and Quilt as Art Form, In Buszek, M.E. (ed). Extra-Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, Duke University Press, pp 99-114.

- Everyone’s Been There’ from Brown, N. (2006) Tracey Emin London:Tate

- See Jones, W., (2006) Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl Great Britain: Chatto & Windus

- Susie MacMurray’s piece “A Mixture of Frailties” is a bridal gown ironically constructed out of 1,400 household gloves in “a kind of cautionary tale about domestic reality” [Each] glove is turned inside out to reveal its “pale downy interior, like flayed skin, they are testament to the vulnerability of humankind.” MacMurray … is fascinated by … moments of change and alchemy, where the point of transition from one thing into another is manifest. … she is constantly seeking the material manifestation at the edge between things. When is it that objects tip from one thing into another? Rom the familiar to the unfamiliar? MacMurray seeks to subvert her materials to contain that moment when we tip into chaos, that moment of frisson when levels of energy are at their strongest and most creative. … Widow (2009), where she individually inserted 43kg of adamantine dressmaker pins painstakingly through a black leather skin forming a seductively glittering evening dress, of human scale, … draws you to the touch yet immediately repels you with its sharp, cold, aggressive points.”

Fig 12

Fig 12

Quotations taken from Soriano, K. (2011) The Eyes of the Skin catalogue essay for The Eyes of the Skin, Agnew’s Gallery, November 9th – December 2nd 2011.

Susie MacMurray’s view on her practice is ‘what is the point of making art that you can completely explain through words?’ The fundamental feeling one experiences when viewing her garment sculptures is one of wanting to touch, especially because of the visual and tactile conundrum between the material qualities and its context.

- Robins’ use of knitting in this context is subversive in that its lack of status draws attention to it and its non-ability to be worn challenges the viewer’s relationship with it. “I use knitting to explore pertinent contemporary issues of the domestic, gender and the human condition. I find knitting to be a powerful medium for self-expression and communication because of the cultural preconceptions surrounding it. My work subverts these preconceptions and disrupts the notion of the medium being passive and benign.” Quote from Artist’s Statement on her website. Accessed 17th November 2012 but no longer available

- Adamson, G. (2007) Thinking Through Craft Oxford: Berg, p4.

- Risatti, H. (2007) A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Expression. Chapeltown: University of North Caroline Press

- Buszek, M.E. (2011) Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art. Duke University Press, p13

- See Craftivism, from Ibid. pp175-240

- The technology behind the 3-D printer is, I think, going to raise further debate as to the relevance of craft in the near future, but as this applied mostly to ‘hard’ crafts (such as ceramics, wood, metal, plastics) rather than textile, it is beyond the scope of this particular essay.

- Developed from military use, soft witching communication and electronic capability is making its way into one-off fashion – ‘wearable art’. See Appendix B

- Jun-ichi Arai has been involved in many exhibitions both in Japan and elsewhere with his innovative fabrics that combine technological advances, modern materials and hand- and industrial processes. He founded Nuno Corporation (now headed by Reiko Sudo) to bring these different elements together and to encourage car component manufacturers, textile designers and artists to think laterally. He has used many practices developed in engineering to inform his cloth development, combining the future with the eternal Japanese aesthetic and sensibility. Jun-ichi Arai prefers to let his work speak for him, but for a profile on this prolific and imaginative designer, see http://gallerygen.com/art/arai.html#BYOGRAPHY Accessed 23rd November 2012

- Reuter, L. (2003) Machiko Agano, Portfolio Collection. Winchester: Telos p27. It is noticeable that neither Arai nor Agano have a website, nor do they often write about their own work. Both seem to prefer to let their work (and other people) do the talking. They are not alone amongst Japanese artists. Even Nuno Corporation write very little about their company. In the books that they have published (Suke Suke is one in a series – see Bibliography), the emphasis is on the fabrics, and the sparse information given is of materials and process, collating the fabrics into aesthetic groups such as ‘like the wind’ or ‘fire’. (The introduction of Suke Suke begins with the words, “Ultra-sheer, filmy wisps of transparency… With suke suke fabrics, what you see is not what you get – only a small part of it.”)

- Kearney, R. (1994) Modern Movements in European Philosophy. Manchester: Manchester University Press, p240

- Ibid. p253

- During the course of my study, I have become aware that weave, for me, is no longer either purely functional or purely an intellectual pursuit. It is a deep level of knowing – a “knowing and understanding .. not only intimately related formally and conceptually, [but] co-dependent and .. essential to any system of communication, including art.” (Risatti, H. (2007) A theory of craft: function and aesthetic expression. Chapeltown: University of North Carolina Press, p9. Weave to me is a means of communication – a method of learning, expressing, and sharing my deepening awareness of fundamental forces in common between plate tectonics and weave.

- Albers, A. (1994) ‘One Aspect of Art Work’ in Albers, A (1979) On Designing Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, p31

Figures

- Theo Moorman hanging – image on Pinterest. (Accessed 20th December 2018) Website for Theo Moorman at: http://www.theomoormantrust.org.uk

- Peter Collingwood PC022 – image from Galerie Besson Available at: http://www.galeriebesson.co.uk/collingwoodcoper.html (Accessed 24th November 2012)

- Amish quilt – http://www.amishcountrylanes.com/Pages/hs6484.shtml (Accessed 20th December 2018)

- Gee’s Bend quilt – http://www.auburn.edu/academic/other/geesbend/explore/catalog/slideshow/pages/q140-03b_JPG.htm (Accessed 20th December 2018)

- Tracey Emin Everyone’s Been Here in Brown, N. (2006) Tracey Emin London: Tate- Modern Artists Series

- Grayson Perry as Claire – image available under search options of Grayson Perry as Claire/images (Accessed 20th December 2018)

- Susie MacMurray A Mixture of Frailties (2004) image available under search options of Susie MacMurray (Accessed 20th December 2018) Website: http://www.susie-macmurray.co.uk

- Freddie Robins Anyway (2002) In the collection of the Castle Museum, Nottingham. Image available at: http://www.freddierobins.com/blog/anyway (Accessed 20th December 2018)

- subTela Jackets. Image by Studio subTela from website. Available at: http://subtela.hexagram.ca/jackets-antics/ (Accessed 20th December 2018)

- Jun-ichi Arai Crocodile (detail) Image from Cooper Hewitt. Available at: http://www.cooperhewitt.org/2012/12/06/crocodile/ (Accessed 20th December 2018)

- Machiko Agano – image from Textile Arts Center. Available at: http://textileartscenter.wordpress.com/2010/07/14/machiko-agano/ (Accessed 24th November 2012)

- Susie MacMurray Widow (2009) http://www.thisiscolossal.com/2018/09/sculptures-by-susie-macmurray/ (Accessed 20th December 2018) Website: http://www.susie-macmurray.co.uk

- Peter Collingwood weaving Macrogauze – image courtesy of Carla Gladstone

APPENDIX A TECHNICAL ADAPTATIONS FOR CREATING ANGLEFELL, SHAFT-SWITCHING AND MACROGAUZE

Anglefell – in order to create an angled line in the weaving that is not perpendicular to the warp, you have to make adjustments to the beater. This is done by ensuring that the beater is able to be moved as if on a central axis. In order to be able to hold the beater in an angled position, U-shaped blocks need to be affixed to the top side horizontal bars of the loom on both sides, t=so that the beater can be put in various positions such as position 1 on the left and position 5 on the right and still work effectively.

Shaft-Switching – following on from a student’s suggestion that it would be nice to move a warp thread from one shaft to another (a fundamental problem in most looms), and from realising that that would allow much more variation in rug design, Collingwood devised a method of doups (loops attached to a lifting mechanism) that would allow one thread to be used normally in the shaft it was threaded in, but also lifted by the doup on another shaft. He refined the technique so that the ‘moving’ war thread was neither threaded in one shaft or another, but would have doups attached to both shafts, enabling either shaft to lift the thread. This gave a greater facility in designing without the need for extra pedals on the loom. His technique was successfully developed commercially onto a loom that is sold in the United States as the Shaft-Switching Loom.

Macrogauzes – in order to create his Macrogauze hangings, Collingwood removed the usual shafts, reed and batten and replaced them with a number of narrow rigid heddles which he put side by side in a special batten. Each rigid heddle was threaded with its own bobbin and hung separately weighted at the back of the loom. The batten was lightweight and suspended on springs so that it could be raised out and lowered to allow for plain weaving. Whenever he wished to take one of the rigid heddle elements out and move it across other sections, he would simply lift the lid of the batten, remove the specific rigid heddle, replace it where required, close the batten lid, adjust the position of the warps at the back of the loom and start weaving again. This was an innovative development for wall-hangings that featured moving warps leading to abstract geometric designs that are now collectors’ items.

Fig 13

Fig 13

Information from personal conversation with Peter Collingwood from 2006 – 2008, a video interview Peter Collingwood, Weaver: In Conversation with Stacey Harvey-Brown, (2008) Complex Weavers, and Technical Notes from Crafts Council Catalogue (1998), Peter Collingwood, Master Weaver Great Britain: Crafts Council.

APPENDIX B

SOFT SWITCH COMMUNICATION AND ELECTRONICS APPLICATIONS

This recent development in integrating soft switch communications and electronics in one-off fashion has been pioneered by Barbara Layne from the Hexagram Institute. She is the Director of Studio subTela which is focused on the development of intelligent cloth structures for the creation of artistic, performative and functional textiles, employing the skills of graduate students from Visual Arts and Engineering at Concordia University and a variety of international collaborators.

“Natural materials are woven in alongside microcomputers and sensors to create surfaces that are receptive and responsive to external stimuli. Controllable arrays of Light Emitting Diodes present changing patterns and texts through the structure of cloth. Wireless transmission systems have also been developed to support real time communication … textiles are used to address the social dynamic of fabric and human interaction.” Barbara Layne

Available at: http://subtela.hexagram.ca/ Accessed 17th November 2012

This work has its origins in military developments. Highly functional but lightweight garments have been developed for soldiers on operations with inbuilt ‘soft switches’ and electrical circuitry for data pads, USB hubs, feedback systems and telecommunications arrays, in order to reduce the weight of batteries and equipment they have to carry. Asha Peta Thompson (Intelligent Textiles Ltd) has been at the forefront of this work and presented some of her work at the Stroud International Textile symposium in May 2011.

Conductive Textiles for Soldier Systems. A Research Fellowship at Brunel University led to the development of soft switches for soft electronics, with a full qwerty keyboard which can be attached to a computer and used in the field (military use). It can also be a sensory fabric which can be incorporated into garments and can be woven in one piece.

A heat fabric system called Heat ™ for integrating low voltage heating elements into woven fabric has been developed that looks, acts, feels and works like an ordinary fabric including being washed in a machine.

Connect ™ is a fabric which transmits power all around the body. The tape can be cut, have a hole in it (i.e. bullet or knife) and it still conducts, re-routing the current to allow for this. They are working with the army to incorporate it into field uniforms for soldiers to replace the 62 AA batteries each soldier has to carry in the field to operate the various equipment he needs. It would also replace the wiring in the current soldier system. The conventional system is bulky, heavy, stiff, broken easily by repetitive bending, can snap, has no redundancy or graceful degradation. The new conductors are arranged on a flat plane and offer greater flexibility as well as being robust.

The fabric can be used to carry power and data. USB hubs put into the fabric with an interface at sleeves, on the shirt, and ballistic vest are all networked together, adding functions such as video camera, GPS, thermal sensors etc. It also successfully streams video, GPS information and environmental data. It also offers insulation, waterproofing, and camouflage.

The soft switching is achieved through using plain weave and different sizes and lengths of floats, with a lot of research having gone into the thickness of the yarn, loop heights etc.

For further information on the pioneering development of soft switching, see http://www.startups.co.uk/intelligent-textiles-asha-peta-thompson.html and http://www.fibre2fashion.com/industry-article/29/2873/intelligent-textiles-reducing-the-burden1.asp (Both accessed 23rd November 2012)

Bibliography

Adamson, G. (2007) Thinking Through Craft Oxford & New York: Berg

Adamson, G. (ed.) (2010) The Craft Reader Oxford & New York: Berg

Albers, A. (1979) On Designing Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press

Albers, A. (1965) On Weaving New York: Dover Publications Inc

Brown, N. (2006) Tracey Emin London: Tate – Modern Artists Series

Colchester, C. (2007) Textiles Today: a global survey of trends and traditions London: Thames & Hudson

Crafts Council Catalogue (1998) Peter Collingwood, Master Weaver Great Britain: Crafts Council

Dormer, P. (ed.) (1997) The Culture of Craft Manchester: Manchester University Press

Gordon, B. (2011) Textiles: The Whole Story London: Thames & Hudson

Greenhalgh, P. (ed.), (2002) The Persistence of Craft London: A & C Black

Granick E.W. (1989) The Amish Quilt Philadelphia: Good Books

Hibbert, R. (2001) Textile Innovation: interactive, contemporary and traditional materials London: Line

Jones, W., Perry, G. (2006) Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl Great Britain: Chatto & Windus

Kearney, R. (1994) Modern Movements in European Philosophy Manchester: Manchester University Press

Mairet, E. (1942) Handweaving and Education London: Faber

Millar, L. (ed.) (2007) Cloth and Culture Now Great Britain: University College for the Creative Arts

Millar, L., Dolley, A. (2001) Catalogue, Textural Space: contemporary Japanese textile art Great Britain: James Hockey Gallery & Surrey Institute of Art & Design University College

Millar, L. (ed.) (2011) Lost in Lace: transparent boundaries Birmingham: Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Monem, N. (ed.) (2008) Contemporary Textiles: the fabric of fine art London: Black Dog Publishing

Moorman, T. (1975) Weaving as an Art Form New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2002) The Quilts of Gee’s Bend – Masterpieces from a Lost Place Atlanta: Tinwood Books

Nuno (1997) Suke Suke: The Emperor’s New Clothes Tokyo: Masaaki Takekura Nuno Corporation (also in the series: Boro Boro (1997); Fuwa Fuwa: strictly lightweight fluff (1998); Shimi Jimi (1998); Kira Kira (1999); Zawa Zawa: the murmer of the unknown (1999)

O’Mahony, M., Braddock, S. (eds.) (1994) Textiles and New Technology 2010 London: Artemis

Quinn, B. (2010) Textile Futures: fashion, design and technology Oxford: Berg

Reuter, L. (2003) Machiko Agano Winchester: Telos Art Publishing Portfolio Collection

Richards, A. (2012) Weaving Textiles That Shape Themselves Marlborough: The Crowood Press

Rissati, H. (2007) A theory of craft: function and aesthetic expression Chapeltown: University of North Carolina Press

Schoesser, M. (2012) Textiles: The Art of Mankind London: Thames & Hudson

Sutton, A. (1985) British Craft Textiles London: William Collins Sons & Co Ltd

Turney, J. (2009) The Culture of Knitting Oxford & New York: Berg